Inventions usually come into being because of necessity and the McKeen Motorcar was an excellent example.

Railroads were expanding rapidly during the latter part of the 1800's. New tracks were being laid all over the western part of the U.S. and people were becoming accustomed to the sound and smoke from steam locomotives. A steam locomotive during the 1860's-1870's cost about $12,000 to $15,000 each depending on configuration. The boilers were fueled usually with coal and sometimes wood. A source for water was necessary along the route and all of these things added to operating costs. To operate a steam locomotive required a large infrastructure because water had to be added about every 50 miles and coal 100-120 miles. This made operating a steam locomotive quite labor intensive. The railroads were making large profits during the country's huge westward expansion but, as a business, they were always looking to keep costs under control.

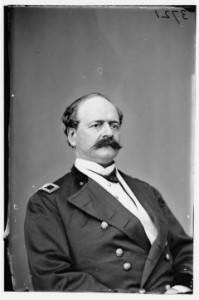

At the turn of the century the Union Pacific began adding shorter less profitable spur lines to their routes and were searching for an economical way to operate. This is when E.H. Harriman, Director of the Union Pacific Railroad and pictured at right, asked William McKeen his Superintendent of Motive Power and Machinery to find a way to lower passenger traffic expenses on the shorter routes.

A Motorcar

McKeen's answer was a revolutionary new motorcar powered by an internal combustion gasoline engine. As you can see from the picture at the top of the page and below, the new car had other distinctive features such as a pointed front end. This was before the word aerodynamic was used and the front ends were referred to as "wind splitters".

Approximately 150 of McKeen's Motorcars were built at the Union Pacific rail yards in Omaha, NE between 1905 and 1917. The first motorcars were built at a Union Pacific owned shop and later at a shop leased to The McKeen Motorcar Company.

In addition to the wind splitter front end and rounded rear end, the vast majority of those built had oval passenger windows which was something new and gave the cars a modern touch. The rounded windows were advertised as being watertight and dust free. There were a number later built with the more conventional rectangular windows with arched tops. Both designs are shown below. The cars were built in lengths of both 55 and 70 feet.

Mechanical Difficulties

Unfortunately there were issues regarding the engine. At the start, 100 horsepower gas engines were used then they were upped to 200 and 300 horsepower.

Unfortunately there were issues regarding the engine. At the start, 100 horsepower gas engines were used then they were upped to 200 and 300 horsepower.This was the era before the automobile explosion and gasoline was cheap but these early gas engines which were built on a marine design proved unreliable and broke down often. The motorcars also had an air-clutch and a two-speed transmission. There was no reverse gear. To run the car backwards (rail cars sometimes must) you had to shut down the engine and manually reverse the cam shaft. The earlier models had power to only the front wheels and operators often complained about a lack of traction.

As time went by some cars were refitted with kerosene engines but it appears many were subsequently re-engined back to gasoline. During the mid 1910's kerosene became cheaper than gasoline. A few were converted to steam power and some to electromotive power in the late 1920's. Heat was provided by steam water and later interior electricity was added with batteries charged by a generator on the engine.

Demand for an Economy on Shorter Routes

When the McKeen Motorcar was introduced the demand was great. Many of the first cars were sold to the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads but it's estimated that about 50 different railroads used the McKeen Motorcar from New York to California. There was a big need for economy on the shorter passenger routes. Although the unreliable engines and clutch difficulties were the major problem with the cars, they were used extensively on the nation's short line railroads and their unique design features certainly made them stand out.

Below is a partial list of smaller railroads that used the McKeen Motorcar;

Ann Arbor RR 5 cars

Arizona Eastern RR 4 cars

Oregon-Washington RR 3 cars

Maricopa-Phoenix RR 2 cars

Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific RR 5 cars

Chicago Great Western RR 4 cars

Central New York Southern RR 2 cars

Houston-Texas Central RR 1 car

One of the finest railroad museums in the country and an excellent source for McKeen Motorcar history is the Nevada State Railroad Museum in Carson City. Check their schedules for rides offered on both the McKeen Motorcar and the 1926 Edwards Rail Car. The museum web site below offers directions and has a schedule of all events. You might also find the short story of the Steam Powered Motorcycle interesting.

(Photos and images from the public domain)

www.nsrm-friends.org

Here is a good site for more information on the McKeen Motorcar.

www.onlinenevada.org/mckeen_motor_car

www.nsrm-friends.org/nsrm44.html